Introduction

After a few scheming years, i had come to view objects as little more than poor-man closures. Rolling a simple (or not so simple) object system in scheme is almost a textbook exercise. Once you’ve got statically scoped, first-order procedures, you don’t need no built-in objects. That said, it is not that object-oriented programming is not useful; at least in my case, i find myself often implementing applications in terms of a collection of procedures acting on requisite data structures. But, if we restrict ourselves to single-dispatch object oriented languages, i saw little reason to use any of them instead of my beloved Scheme.

Things started to change recently due to my discovering the pleasures of Smalltalk. First and foremost, it offers a truly empowering integrated ambient to live and develop in. Second, if you’re going to use objects, using the simplest, cleanest syntax will not hurt. Add to that some reading on the beautiful design principles underlying Smalltalk, and one begins to wonder if closures aren’t, in fact, poor-man objects–or at least i do, whenever i fall in an object-oriented mood (i guess i’m yet not ready to reach satori).

But Scheme is not precisely an ugly or bad designed language, so i needed some other reason to switch language gears for my OO programming. I knew there’s more than encapsulation or subtype polymorphism in object-land from my readings on CLOS (the Common Lisp Object System), or on Haskell’s type classes (and its built-in parametric polymorphism), but i was after something retaining Smalltalk’s elegance. And then i remembered that, when i was a regular lurker in the Tunes project‘s mailing lists and IRC channel, a couple of smart guys were implementing an OO language whose syntax was smalltalkish. That language (which, if memory servers, started life with the fun name who me?) has evolved during the last few years into a quite usable programming environment named Slate, started by Lee Salzman and currently developed and maintained by Brian Rice.

I’ve been reading about Slate during the last few days, and decided to learn it. What motivated me was discovering how Slate goes beyond mainstream object-oriented programming by incorporating well-known (but hardly used) and really powerful paradigms. In short, Slate improves Smalltalk’s single-dispatch model by introducing and combining two apparently incompatible technologies: multiple dispatch and prototype-based programming. To understand the whys and hows of Slate, there’s hardly a better way than reading Lee Salzman’s Prototypes with Multiple Dispatch. The following discussion is, basically, an elaboration of Lee’s explanation on the limitations of mainstream OO languages, and how to avoid them with the aid of PMD.

(Note: click on the diagrams to enlarge them, or, if you prefer, grab a PDF of the whole set.)

Fishes and sharks

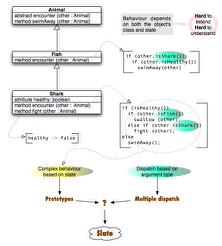

Let’s start by showing why on earth would you need anything beyond Smalltalk’s object system (or any of its modern copycats). Consider a simple oceanographic ecosystem analyser, which deals with (aquatic) Animals, Fishes and Sharks. These are excellent candidates for class definitions, related by inheritance. Moreover, we are after modeling those beasts’ behaviours and, in particular, their reactions when they encounter each other: each time a Shark meets a Fish of other species, the Shark will swallow the other Fish, while when a Shark meets Shark they will fight. As a result of such fighting, Sharks get unhealthy, which regrettably complicates matters: wound sharks won’t try to eat other fishes, and will swim away other sharks instead of fighting them. The image on the left provides a sketchy representation of the code we need to model our zoo. Waters are quickly getting muddled implementation-wise.

Let’s start by showing why on earth would you need anything beyond Smalltalk’s object system (or any of its modern copycats). Consider a simple oceanographic ecosystem analyser, which deals with (aquatic) Animals, Fishes and Sharks. These are excellent candidates for class definitions, related by inheritance. Moreover, we are after modeling those beasts’ behaviours and, in particular, their reactions when they encounter each other: each time a Shark meets a Fish of other species, the Shark will swallow the other Fish, while when a Shark meets Shark they will fight. As a result of such fighting, Sharks get unhealthy, which regrettably complicates matters: wound sharks won’t try to eat other fishes, and will swim away other sharks instead of fighting them. The image on the left provides a sketchy representation of the code we need to model our zoo. Waters are quickly getting muddled implementation-wise.

On the one hand, subtype polymorphism based just on the object receiving the encounter message: we need, in addition, to take into account the argument’s concrete type to implement the desired behaviour. This is a well-known issue in single-dispatch languages, whose cure is, of course, going to multiple dispatching (see below). In particular, we want to avoid the need to modify existing classes whenever our hierarchy is extended.

On the second hand, varying state (exemplified here by the Shark’s isHealthy instance variable complicates the implementation logic. As we will see, prototype-based languages offer a way to factor out this additional complexity.

Beyond single-dispatch

The need to adjust behaviour on the basis of the type of both a message receiver and its arguments arises frequently in practice. So frequently, that a standard way of dealing with it has been christened as the Visitor design pattern. The technique, also known as double-dispatch, is well known: you can see, for instance, how it’s applied to arithmetic expressions in Smalltalk, or read about a generic implementation of multimethods in Python (which also includes a basically language-independent discussion on the issues at hand). If you happen to be a C++ programmer, you may be tempted to think that global functions and overloading solve the problem in that language. Well, think twice: a proper implementation of multiple dispatch in C++ needs of RTTI and templates, as shown in this article.

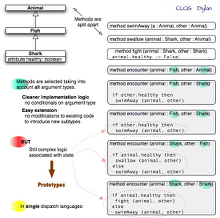

CLOS and Dylan are two examples of languages solving the issue from the onset by including support for multi-methods. The idea is to separate methods from classes (which only contain data slots). As shown in the pseudo-code of the accompanying figure, methods are defined as independent functions with the same name, but differing in their arguments’ types (in CLOS, a set of such methods is called a generic function). When a generic function is called, the system selects the actual method to be invoked using the types of all the arguments used in the invocation. The encounter generic function in our running example provides a typical example, as shown in the figure on the right. The benefits of having multi-methods at our disposal are apparent: the code is simpler and, notably, adding new behaviours and classes to the system does not need modifications of existing code. For instance, we can introduce a Piranha, which eats unhealthy sharks instead of swimming away from them, by defining the requisite class and methods, without any modification whatsoever to the already defined ones.

CLOS and Dylan are two examples of languages solving the issue from the onset by including support for multi-methods. The idea is to separate methods from classes (which only contain data slots). As shown in the pseudo-code of the accompanying figure, methods are defined as independent functions with the same name, but differing in their arguments’ types (in CLOS, a set of such methods is called a generic function). When a generic function is called, the system selects the actual method to be invoked using the types of all the arguments used in the invocation. The encounter generic function in our running example provides a typical example, as shown in the figure on the right. The benefits of having multi-methods at our disposal are apparent: the code is simpler and, notably, adding new behaviours and classes to the system does not need modifications of existing code. For instance, we can introduce a Piranha, which eats unhealthy sharks instead of swimming away from them, by defining the requisite class and methods, without any modification whatsoever to the already defined ones.

On the downside, we have still to deal with the complications associated with internal state. Enter the magic world of prototype-based systems.

The ultimate dynamic

If you like dynamic languages, chances are you’ll find prototype-based system an almost perfect development environment. Prototype-based languages emerged as an evolution of Smalltalk with the invention of Self by David Ungar and Randall B. Smith during the late eighties. The key idea behind Self is noticing that, most of the time, class definitions needlessly coerce and complicate your object model.

A class definition becomes a contract to be satisfied by any instance, and it is all too easy to miss future or particular needs of your objects (class-based inheritance is just a partial solution to this problem, as shown, for instance, by the so-called fragile base class problem). But, if you look around you, objects change in internal behaviour and data content continously, and our attempts at distilling their Platonic nature are often in vain.

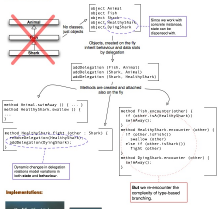

In prototype-based programming, instead of providing a plan for constructing objects, you simply clone existing instances and modify their behaviour by directly changing the new instance’s slots (which provide uniform access to methods and state). New clones contain a pointer to their parent, from which they inherit non-modified slots: there is no way to access state other than via messages sent to instances, which simplifies tackling with state.

Class-based languages oblige you to keep two relationships in mind to characterize object instances: the “is-a” relationship of the object with its class, and the “kind-of” relationship of that class with its parent. In self, inheritance (or behaviour delegation) is the only one needed. As you can see, Self is all about making working with objects as simple as possible. No wonder Ungar and Smith’s seminal paper was titled Self: The Power of Simplicity. Needless to say, a must read.

The figure on the left shows how our running example would look in selfish pseudo-code. As promised, state is no longer surfacing in our method implementation’s logic. Unfortunately, we have lost the benefits of multi-methods in the process. But fear not, for, as we will see, you can eat your cake and have it too. Instead of pseudo-code, you can use Self itself, provided you are the happy owner of a Mac or a Sun workstation. Or you can spend 20 fun minutes seeing the Self video, which features the graphical environment accompanying the system. Like Smalltalk, Self provides you with a computing environment where objects are created, by cloning, and interact with you. The system is as organic and incremental as one can possibly get.

The figure on the left shows how our running example would look in selfish pseudo-code. As promised, state is no longer surfacing in our method implementation’s logic. Unfortunately, we have lost the benefits of multi-methods in the process. But fear not, for, as we will see, you can eat your cake and have it too. Instead of pseudo-code, you can use Self itself, provided you are the happy owner of a Mac or a Sun workstation. Or you can spend 20 fun minutes seeing the Self video, which features the graphical environment accompanying the system. Like Smalltalk, Self provides you with a computing environment where objects are created, by cloning, and interact with you. The system is as organic and incremental as one can possibly get.

Of course, you’re not limited to Self. For instance, Ken Dickey fleshed up Norman Adams’ saying that objects are poor man closure’s by offering a prototype-based object system in Scheme, and, more recently, Neil Van Dyke has released Protobj. And you have probably already used a very popular language in the family: Javascript. The list goes on, albeit, unfortunately, many of these languages lack either Self’s nice integrated environment, or a portable, up-to-date implementation. Slate to the rescue.

The best of both worlds

Prototyping and multiple dispatch are, at first sight, at odds. After all, method dispatching based on arguments’ type needs, well, a type for each argument, doesn’t it? As it happens, Lee Salzman and Brian Rice have envisioned a way of combining the power of both paradigms into Slate. In fact, proving how this is possible is the crux of Lee’s article. In addition, Slate aims at providing a complete development environment in the vein of Smalltalk or Self. Too good to be true? In future installments of this blog category, we’ll see how and why it’s true, but, if you cannot wait, just run-not-walk to Slate’s site. You’ll have a great time.

Tags: common lisp, learning, lisp, programming, scheme, slate, smalltalk

February 5, 2006 at 2:39 pm

[...] Closures, Objects, and Poor Men [link via programming musings] [...]

February 6, 2006 at 2:19 am

well done!

February 6, 2006 at 5:23 am

looks like an simple pattern matching for me :)

using erlang:

% encounter(Who, Whom) encounter(Who = {shark, SharkState}, Whom = {shark, OtherSharkState}) when member(healthy, SharkState) -> fight(Who, Whom); encounter(Who = {shark, SharkState}, Whom = {fish, FishState) -> swallow(Who, Whom); encounter(Who = {_, SharkState}, Whom = {_, FishState}) -> swimAway(Who).February 7, 2006 at 1:25 pm

What about encapsulation? That’s one of the strongest motivations for using OOP, but you completely forgot about it.

If methods are external to the class, it means that “things” (the methods) outside of a class will have to know about a class’es internal implementation.

This means that if I change a class’es implementation, the impact of this change is not contained (encapsulated) inside this class. In fact, I couldn’t predict the impact of such a change.

February 7, 2006 at 11:08 pm

Very well done…

Great tutorial!

February 8, 2006 at 1:18 am

Daniel,

CLOS, for instance, provides both multi-methods and accessors to a class slots (to aid in encapsulation). Whether encapsulation (forced by the language rather than by convention) is ‘one of the strongest motivations for using OOP’ is highly debatable, though. I won’t enter right now in such a debate. Anyway, defining OOP is one of those religious issues with no right answer, but let me just point out that you would have a hard time arguing that CLOS or Self are not object-oriented languages ;).

Regarding the benefits (or lack thereof) of encapsulation, i would recommend this recent news post in comp.lang.smalltalk whose spirit i basically endorse.

February 9, 2006 at 11:16 am

[...] Beyond mainstream object-oriented programming [...]

February 16, 2006 at 1:58 pm

Interesting post (on comp.lang.smalltalk), I will read it over again when I have more time to think about it.

I come from a school where I always heard that “OOP is founded on 3 pillars: encapsulation, inheritance and polimorphism”, but I see this is not a consensus.

I’m fluent in Java, but know nearly nothing about Smalltalk. I’ll try to learn more about it to see if I can see this issue under a different perspective.

Thanks for the discussion.

February 23, 2006 at 12:25 am

hmm, just a note: Slate was Lee’s pet project when Brian came helping. Lee did all the language features while Brian made a lot of lib work.

then Lee lost interest, and abandoned the project, but still this is not fair/correct as it is:

” into a quite usable programming environment named Slate, developed and maintained by Brian Rice.”

February 23, 2006 at 12:54 am

Lee definitely deserves most of the credit for making Slate what it is today, although this history of Slate is a little more complicated than “former slater” indicates. Mostly, that the vision for Slate to be a next generation type of Squeak became the reason for turning the PMD algorithm into a Smalltalk dialect, and then later to channel Lee’s compiler experiments into it. Things diverged when he realized that he didn’t want to maintain a widely-used system – to him, it was just an outlet at a hobby level.

Of course, he is well beyond me (and most everyone else) in systems programming skill and so this creates a certain imbalance which naturally makes me look like I co-opted it when I was doing all the talking on the mailing list and making releases and so forth. I don’t want to give that impression and I’d rather be ( and be known as ) a coordinator of much smarter people than I than the “lone hero” of a little language-island.

Anyway, I just helped jao rephrase it fairly. Hopefully this keeps things clear.

March 29, 2006 at 9:54 am

I played around with Slate for a little bit a year or so ago. Multi-dispatch coupled with prototypes is a very appealing concept to me.

I was afraid Lee Salzman had left though, but wasn’t sure. I’d be curious to hear Lee’s take on his loss of interest in Slate.

Unfortunately, Slate seems to have a bleak future. There just isn’t that much interest in it based on the mailing list and irc archives. That coupled with the loss of Lee and (AFAIK), still no environment that Smalltalkers are used to doesn’t bode well for the project.

Factor is another language that its creator has stated is partially inspired by Slate. I think Forth is the primary inspiration though.

It’s too bad that something like Slate couldn’t have at least gotten to a state where it could’ve been explored by Smalltalkers.

The social environment surrounding Slate was always less than optimal. That’s about as diplomatic I can get on that subject.

But hopefully Slate can get a second wind at some point in time.

July 22, 2006 at 5:53 pm

[...] Beyond mainstream object oriented programming [...]

February 28, 2007 at 5:11 am

[...] Beyond Mainstream Object Oriented Programming [...]